The Bad Politics and Bad Policy of Republicans’ Effort to Strip Away Health Insurance… And It’s Time to Go to the Mattresses

It’s a day ending in “y,” so Republicans are trying to make draconian cuts to American’s health insurance. Again.

The House Republicans released their reconciliation bill, which – consistent with expectations – proposes deep cuts to Medicaid in a 160-page section dedicated to health. The bill goes to markup today (Tuesday).

So, what do these Medicaid cuts look like? The House Republicans seek to impose stricter eligibility verification, citizenship checks, tougher screenings on providers seeking reimbursements, reductions in federal Medicaid funds to states that offer coverage to undocumented immigrants, and – you guessed it – work requirements. And interestingly – unlike the 2018 Arkansas work requirement for 30-49-year-olds that was struck down in court, the current proposed Medicaid work requirement applies to a much larger swath of the public: 19 to 64-year-olds.

Now, the bill does exclude some previously discussed and more controversial provisions: it does not impose per capita caps on Medicaid spending, and it does not appear to reduce the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (or FMAP), which would have likely implicated 12 states’ Medicaid trigger laws.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office evaluated the impact of these proposed cuts and estimated that it would result in 8.6 million fewer people being insured. What’s more, once accounting for the expiration of the Biden Administration’s enhanced marketplace subsidies (the expiration of which the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated would cause premiums to increase an average of over 75%), the CBO estimated that a staggering 13.7 million fewer people would be insured. And these numbers may be undercounts because they assume that states can make up for some of these federal reductions, to a degree that may be unrealistic especially amid economic downturn.

Keep in mind, the reason why they want to make these cuts is to support tax cuts for America’s wealthiest citizens.

Now let’s dive in to the bad policy, bad evidence, and bad politics of the proposed cuts.

The Bad Policy: Medicaid Cuts Are Harmful to Everyone

Medicaid is a critical health program covering about 1 in 5 Americans overall. What’s more, it covers 41% of births, 63% of nursing home residents, and 39% of children. Imposing massive cuts to it is, to quote our previous president, a BFD.

And when people lose health insurance, their health needs don’t go away. So, what ends up happening to them? They wait until they get sicker and sicker and can no longer avoid care, at which point they rely on emergency department care, which is quite expensive and also means more crowded emergency department waiting rooms when other, privately insured patients are also seeking care for emergent conditions. People who are low-income cannot pay thousands of dollars in medical bills, so hospitals take on uncompensated care. While academic medical centers like UPMC or New York Presbyterian can find ways to accommodate this uncompensated care, that is not true for less resourced practices such as rural hospitals, which are struggling to stay open.

Take the example of Spencer Hospital in Iowa, in the town of Spencer, which has a population of just over 11,000. It is one of the few hospitals in Iowa that continue to offer inpatient psychiatric care, but to do so, it’s dependent upon Medicaid payments. After all, while 11% of the non-psychiatric inpatients are on Medicaid, 40% of the psychiatric inpatients are. It already operates at a deficit, and there are questions as to whether it would be able to stay afloat.

Spencer Hospital is not alone – far from it. Between 2005 and 2023, 146 hospitals in rural counties either completely closed or were converted to non-acute care. This number has since ticked up to 151 hospitals.

These rural hospital closures are becoming all too common in recent years. And when the nearby hospital closes, everyone – the publicly insured and the privately insured alike – suffers.

Think you might be having a cardiac event? Sorry, the local hospital closed so you’ll have to drive an extra five miles.

Giving birth? Good luck, because even more rural hospitals have closed their labor and delivery wards. And of course, all of his circles back to social determinants of health because it places more significant demands on patients, especially low-income patients, to have a means of transportation for in-person care, employment flexibility for a now more arduous experience of seeking medical care, and home broadband for telemedicine, and there are geographic, racial, and socioeconomic disparities in this access.

The Bad Evidence: Medicaid Work Requirements Increase Administrative Burden but Do NOT Increase Employment

I used to say that Medicaid work requirements were a solution in search of a problem, but I’ve since realized that they’re actually a solution to a different problem: government provision of health insurance to the poor.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal in defense of the legislation, Rep. Brett Guthrie wrote, “When so many Americans who are truly in need rely on Medicaid for life-saving services, Washington can’t afford to undermine the program further by subsidizing capable adults who choose not to work. That’s why our bill would implement sensible work requirements.”

Embedded in this argument is a common Republican narrative, that there are many Medicaid beneficiaries who are essentially cashing in on their health benefits and opting out of the workforce. Of course, conservative narratives about welfare recipients are not new (remember “welfare queens”?). And of course, American politics seems to operate in a post-truth world these days. But nevertheless, let’s take a look at the voluminous body of evidence that establishes well why such policies are fundamentally misguided, do not serve an allegedly intended purpose of increasing workforce participation (though they may serve an actual intended purpose of reducing Medicaid enrollment), and harm patients through the imposition of administrative burden that results in coverage losses.

In my health politics and policy courses, I teach on the work of Harvard physician and researcher Benjamin Sommers and his coauthors, who examined the Arkansas Medicaid work requirement, which was implemented in June 2018. By early 2019, 18,000 adults had been removed from the Medicaid program due to noncompliance, typically due to their not submitting the required documentation of their work hours or exemption. But while there was ultimately found to be a significant (6.8%) decline in the insured rate, there was no increase in employment or civic engagement.

So, what accounted for the coverage losses? Administrative burden, or the experience of administrative barriers (learning costs, compliance costs, psychological costs) in seeking to access benefits.

Let’s start with the learning costs. Sommers and his coauthors found through a survey of Arkansans within the category at which the work requirement was directed, just 53% of survey respondents had even heard of the work requirement and just 21.8% of survey respondents thought that the work requirement applied to them, while 44.2% weren’t sure. And it’s hard to expect that people will document their work hours if they do not believe this to be a requirement.

Now let’s look at the compliance costs. The program was not initially set up to be a preferred reporting method. In fact, researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation identified the process according to which one would document their work or exemption. I’m an administrative burden scholar and it still made my head explode.

To first set up an account on Arkansas Works, there was an 8-step process that required 5 security questions. Then they had to link the Single Sign On account to the health care coverage account, which required three additional steps and they had to enter online a reference number mailed or emailed to them. Then there were 13 separate steps to report work hours, with additional steps required if beneficiaries held more than one job, and there were still 11 separate steps to report volunteer hours or an approved exemption. And all of this documentation is particularly difficult if one is maintaining inconsistent work hours or doing gig work.

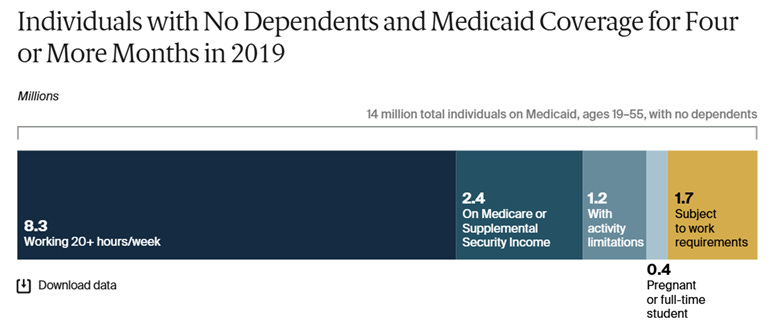

This is all highly burdensome, but why wouldn’t it increase employment? The Commonwealth Fund analysis offers insights here. Examining 14 million Medicaid recipients ages 19-55 with no dependents in 2019, they find that 8.3 million were already working the required 20+ hours per week, another 2.4 million were on Medicare or SSI, 1.2 million had activity limitations, and 0.4 million were full-time students. That leaves just 1.7 million people who were on Medicaid and not already fulfilling a requirement or exempt. That’s just 12% of Medicaid beneficiaries. And that estimate is actually higher than that retrieved through Kaiser Family Foundation analysis, which finds that just 8% of Medicaid beneficiaries are not working the required hours and are not exempt.

Medicaid work requirement plays well into the “personal responsibility” and Horatio Alger narratives that Americans should pull themselves up by their bootstraps, but the plain reality based on evidence from academic researchers and policy organizations (see also the analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities) is that most Americans are doing their best to do just that but are still unable to make ends meet in employment that offers health benefits.

The Bad Politics: People Across the Ideological Spectrum Like Medicaid

Congress scholar David Mayhew famously declared that members of Congress are single-minded seekers of reelection. Toward that end, we would expect that legislators would pursue policies that are broadly popular (potentially even to the exclusion of the evidence basis – and admittedly, the work requirements may fall into that camp).

But efforts to reduce Medicaid investments are broadly unpopular! The Kaiser Family Foundation tracking poll finds that 42% of Americans want to increase Medicaid funding and another 40% want to keep it where it is. So, we’re at 82% of Americans wanting the status quo or better, while just 17% wanted to see it reduced

And that’s not just Democrats. Even among Republicans, 67% of respondents wanted to preserve or increase Medicaid funding. Even 65% of Trump voters want to preserve or increase Medicaid funding! What’s more, most Americans see through the Republicans’ tactics, with 75% of total survey respondents seeing the proposed Medicaid cuts as a means to reduce government spending rather than a way to improve the Medicaid program.

Perhaps it is unsurprising that Medicaid is so overwhelmingly popular across the ideological spectrum: Democrats are broadly favorable toward government investments in health insurance, and red states benefit from Medicaid enormously, whether looking at FMAP, the protection of rural hospitals, or provision of benefits to help people with substance use disorder amid the opioid crisis, which has particularly hit states like West Virginia.

There are good political reasons for Senate HELP Committee Chair Bill Cassidy to reject Medicaid cuts, because Louisiana is the state with the highest percent of births financed by Medicaid. What’s more, Louisiana has the nation’s second largest share of its population on Medicaid, making the proposed cuts especially consequential for this especially consequential senator. This is an issue that should hit home – and he’s up for reelection next year.

Starving the beast to accommodate tax cuts for the wealthy is a tale as old as time – or at least a tale older than I (as I like to joke with my students when making dated references in class). And providing the evidence behind Medicaid’s popularity or the ineffectiveness of work requirements may have limited utility when, to quote Upton Sinclair (whose The Jungle may be depressingly relevant amid reductions to food safety inspections), “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

What Do We Do About It?

So, where do we go from here?

Based on a fairly competitive Cook Partisan Voter Index (PVI) (no more than R+6) and average to heavy Medicaid reliance, I identified 35 House districts to contact and select states whose senators are up for reelection.

AZ-01: David Schweigert

AZ-02: Eli Crane

AZ-06: Juan Ciscomani

CA-03: Kevin Kiley

CA-22: David Valadao

CA-41: Ken Calvert

CO-08: Gabe Evans

FL-04: Aaron Bean

FL-15: Laurel Lee

FL-27: Maria Elvira Salazar

FL-28: Carlos A. Gimenez

IA-01: Mariannette Miller-Meeks

IA-02: Ashley Hinson

IA-03: Zach Nunn

MI-04: Bill Huizenga

MI-07: Tom Barrett

MI-10: John James

NC-06: Addison McDowell

NC-09: Richard Hudson

NC-13: Brad Knott

NE-02: Don Bacon

NJ-02: Jefferson Van Drew

NY-01: Nick LaLota

NY-02: Andrew Garbarino

NY-17: Michael Lawler

OH-10: Mike Turner

OH-15: Mike Carey

PA-01: Brian Fitzpatrick

PA-07: Ryan Mackenzie

PA-08: Robert Bresnahan

PA-10: Scott Perry

TX-15: Monica De La Cruz

VA-02: Jennifer Kiggans

WI-01: Bryan Steil

WI-03: Derrick Van Orden

Alaska: Dan Sullivan

Iowa: Joni Ernst

Louisiana: Bill Cassidy

Maine: Susan Collins

Montana: Steve Daines

North Carolina: Thom Tillis

You may call the Capitol Switchboard at (202) 224-3121 and they will connect you with the appropriate member. To be maximally effective, it is important that you contact YOUR member. With a narrowly divided House, peeling off any vote is impactful.

Medicaid expansion literally saves lives. It’s time to defend it.

“[A]ll of his circles back to social determinants of health” reads as though it should be “this” instead of “his.”